Introduction

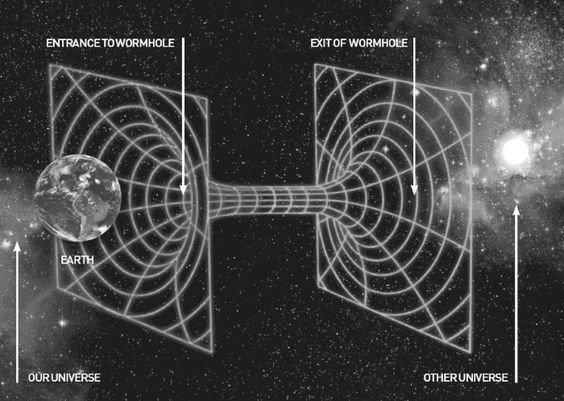

A black hole is a region of spacetime where gravity is so strong that nothing—no particlesor even electromagnetic radiation such as light—can escape from it.The theory of general relativity predicts that a sufficiently compact mass can deform spacetime to form a black hole.The boundary of the region from which no escape is possible is called the event horizon. Although the event horizon has an enormous effect on the fate and circumstances of an object crossing it, it has no locally detectable features. In many ways, a black hole acts like an ideal black body, as it reflects no light.Moreover, quantum field theory in curved spacetime predicts that event horizons emit Hawking radiation, with the same spectrumas a black body of a temperature inversely proportional to its mass. This temperature is on the order of billionths of a kelvin for black holes of stellar mass, making it essentially impossible to observe.

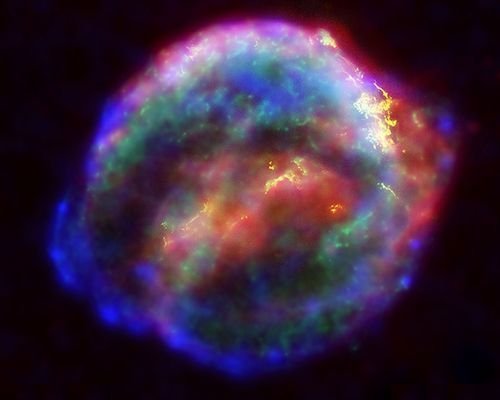

Simulation of gravitational lensing by a black hole, which distorts the image of a galaxy in the background

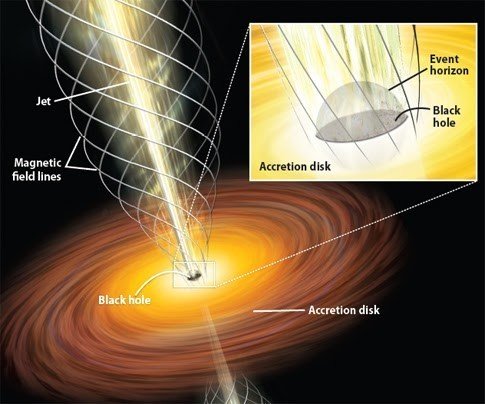

Event Horizon

The defining feature of a black hole is the appearance of an event horizon—a boundary in spacetime through which matter and light can pass only inward towards the mass of the black hole. Nothing, not even light, can escape from inside the event horizon. The event horizon is referred to as such because if an event occurs within the boundary, information from that event cannot reach an outside observer, making it impossible to determine whether such an event occurred.

As predicted by general relativity, the presence of a mass deforms spacetime in such a way that the paths taken by particles bend towards the mass.At the event horizon of a black hole, this deformation becomes so strong that there are no paths that lead away from the black hole.

To a distant observer, clocks near a black hole would appear to tick more slowly than those further away from the black hole.Due to this effect, known as gravitational time dilation, an object falling into a black hole appears to slow as it approaches the event horizon, taking an infinite time to reach it.At the same time, all processes on this object slow down, from the view point of a fixed outside observer, causing any light emitted by the object to appear redder and dimmer, an effect known as gravitational redshift. Eventually, the falling object fades away until it can no longer be seen. Typically this process happens very rapidly with an object disappearing from view within less than a second.

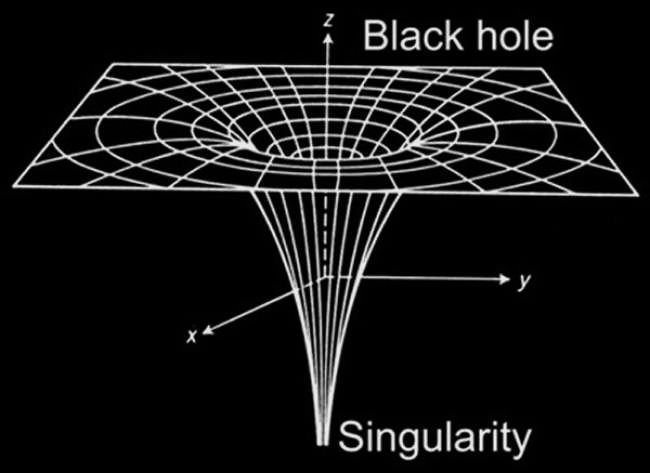

Singularity

At the center of a black hole, as described by general relativity, may lie a gravitational singularity, a region where the spacetime curvature becomes infinite. For a non-rotating black hole, this region takes the shape of a single point and for a rotating black hole, it is smeared out to form a ring singularity that lies in the plane of rotation. In both cases, the singular region has zero volume. It can also be shown that the singular region contains all the mass of the black hole solution. The singular region can thus be thought of as having infinite density.

Observers falling into a Schwarzschild black hole (i.e., non-rotating and not charged) cannot avoid being carried into the singularity, once they cross the event horizon. They can prolong the experience by accelerating away to slow their descent, but only up to a limit. When they reach the singularity, they are crushed to infinite density and their mass is added to the total of the black hole. Before that happens, they will have been torn apart by the growing tidal forces in a process sometimes referred to as spaghettification or the “noodle effect”.

Contact information

Name: Yuvraj Singh Chauhan

Roll.no: 20191CSE0718

Section: PC18